Grief Dissolves Opposites

I frequently joke that being a philosopher and a parent is quite laborious because I dedicate an inordinate amount of mind power to thinking about the form and content of children’s tv, movies, and books. Surrounded by children’s entertainment, I find myself almost always analyzing texts that were never intended for such treatment. But this is one of the fun things about philosophy: “big ideas” often reside in objects that are usually overlooked by scholars.

Take Hippopposites by Janik Coat. A fun book in which the author places a bulbous and minimalistic hippopotamus in scenes intended to highlight adjectives. Each posing hippo faces off with another version of the same hippo on the neighboring page so as to juxtapose two adjectives and teach that they are opposites.

For example, Coat presents a tiny hippo next to a tall skyscraper in order to generate the adjective “small.” On the next page, we see the hippo in close-up and beside a gray bug (or maybe a leaf?). This is “large.” Small and Large are opposites. That’s lesson 1. Throughout the book we encounter clever illustrations of the opposition between light and heavy, full and empty, thin and thick, positive and negative, and so on.

There are three pairs here, however, that I do not understand as opposites. Three pairs that have made me sit for long stretches of time deconstructing and reconstructing my understanding of what precisely opposites are, how we construct them, and recollecting when we first learn of the societally sanctioned opposites such as the ones I’ve already named.

I want to share these three, to my mind, non-opposites in order to make a proposal for how we can critically engage with the concept and demonstration of opposites from here on out. As it turns out, opposites are quite close to one another. Almost even intimate. And this intimacy undoes the dichotomous and even antagonistic dimension that we frequently and unthinkingly attribute to these things we call opposites.

Though it might not be apparent to you, all of this work is in service of rethinking grief. Can we come to know grief through its opposite, or through deliberating on what precisely would count as its opposite? Once a possible pairing has presented itself, are we then in a position to find the intimacy between grief and its other, thereby, in turn, seeing grief in a new way?

Part 1: Close-reading Hippopposites

The three pairs in Coat’s children’s book that have caused me all this fuss are: bright/dark, dotted/striped, and front/side. A longer version of this blogpost would likely also tarry with free/caged and alone/together, but we’ll stick with the shorter list here.

Dotted/Striped

Two things of note here. First, stripes and dots are simply not opposed to one another. They don’t function as two sides of a continuum between which exists the totality of shaped patterns. Second, neither dots nor stripes seem to have an opposite shape. They belong to a family of objects that are opposite-less. This second point is the thought-provoking one insofar as the existence of objects that have no opposites makes me realize that opposites are not necessary. Not everything must have an opposite. If this is true, then the entire notion of “opposite” slides into the category of instrumental concepts, concepts that are produced in order to achieve a certain act in the world. We might, for example, think of dots and stripes paired as opposites in order to make a typology of fashion, one that reveals how certain types of people are more drawn to either stripes or dots. Interesting as that is, there is no hard and fast opposite here.

Lesson 1: Not all opposites are opposites. Opposites are not necessary. Pairs posed as opposites may disguise ideological or pragmatic concerns.

Bright/Dark

The word “bright” forms the scruple here. Were it “light,” then I would probably accept the pairing. Light is Dark’s opposite. Despite times when the two mingle with one another (dusk, dawn), these two states form a continuum of lightedness, from fully lit, on one side, to not lit at all, on the other side. Dark is the absence of light. Light can also be the absence of dark, but the issue of the shadow disturbs the symmetry. Nonetheless, were we to ask 100 people, “What is the opposite of Dark,” I feel confident that 90 or more people would respond, “Light.”

But we don’t get “light” here. We get “bright.” Bright is a quality of light. True, if something is bright then it cannot be dark. But is dark the opposite of bright? Why not “dim”? Bright is light turned up to the max and dim is light turned down to the minimum. Complete darkness seems to be off the continuum altogether.

This case presents the problem of “close enough.” As an educational book, the introduction of “bright” offers a new, less-common word for new readers. The pedagogical merit seems to encourage us to look the other way and, though we feel some discomfort in the pairing of bright and dark, we submit to their title as opposites for the better good. We want young people to read and think about concepts. This one is close enough.

Lesson 2: Each side of the continuum has at least one cognate that, once it enters the picture, complicates the precision of the pairing of opposites. It is possible, however, to get “close enough,” to form a pair of opposites that may not be 100% opposed but are, rather, close enough.

Front/Side

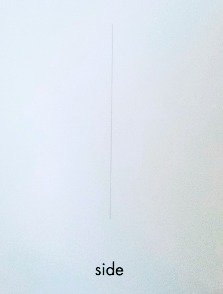

For this one, Coat gives us our by-now-familiar red hippo on the left-hand page with the subtitle, “Front.” The right page contains a thin, vertical, black line above the subtitle, “Side.” What’s going on here?

After thinking about it for a while, the possibility arises that the thin line is in fact our friendly hippo in profile. It is, after all, a two-dimensional drawing. Were it to rotate 90-degrees, its hippo shape would shrink to a single line until disappearing completely (since, of course, two dimensional objects have no width, which is to say less width than that of a line).

The neat thing here is that Coat is prompting children and adults to consider hippo as a picture in a book, a two-dimensional art-object placed on a blank canvas. We get a meta-art lesson here and learn to manipulate the art-object in our minds by imagining what would happen if we viewed the hippo from the side. This is a great mental exercise.

And yet, the two key terms are not opposites. Why is “front” not paired with “back,” which may be its more familiar pair? Could we make an argument that the opposite of “side” is really “center”? Sides, or the peripheral fringes of a territory, are directly opposed to the center of the circle. Side/Center :: Front/Back.

So we are again in the ballpark of “Close enough,” insofar as we recognize the mental gymnastics accomplished by the meta-art manipulation of the two-dimensional hippo and therefore mute our argument about side/center and front/back.

Lesson 3: just because a proposed “opposite” appears within a book about opposites doesn’t mean that it is necessarily an opposite. Its presence in the book may serve another pedagogical purpose altogether. That’s fine. But how, then, are we to build a sturdy definition of opposites when these “close enough” pairings populate the pages of this book?

Part 2: Grief’s Opposite?

In order to halt momentum before getting too analytical, I will stop the close reading and simply say that this children’s book has made me doubt that opposites really exist. Or, rather, I now wonder what are opposite? Are opposites not already unified in a way that we might assume opposites could never truly be? If opposites oppose each other, then how do we account for their status as pairs. Small and large are opposites, but they are united as a pair. In that pairing, they are close together. They are bound by a kind of negative magnetism (opposites attract). Ultimately, this is the lesson I have learned from this book. Opposites are intimate, and that intimacy undoes certainties about what individual words mean and how they function in the world.

This matters to me because I am daily faced with grief. I can admit that I do not enjoy the pain of grief. I would rather not be grieving, for a number of reasons. As such, I occasionally start to imagine the opposite state. What is grief’s opposite?

Ease?

Ignorance?

Bliss?

Lightness?

Certainty?

While I frequently do not feel any of those things while grieving, I don’t think any one of them constitutes grief’s opposite. Perhaps grief, like dots and stripes, belongs to that family of things that has no true opposite?

Or maybe grief is the force that undoes the very notion of opposites? A quick test case is the typical binary Life / Death. Grief has utterly baffled the supposedly strict dichotomy formed by these two states. A version of me certainly died after my father died. And then another version died when my son died. Yet I still live. And these dead loved ones continue to live in our family dynamic. My wife and I tell Finlay and Phalen stories to our 5-year-old every night. His picture adorns many rooms in our house. “Finlay” was one of Ren’s—our youngest son’s—first words. Joanne’s creative grief project “Finlay’s Garden” sends honey and tea across the country, thereby introducing Finlay to others. Finlay lives, albeit not in the way that I want. My father lives in me as I parent, though I wish he was physically here to talk about parenting with me. Test result: grief compels a fundamental remapping of the relationship between life and death. Whatever map you happen to develop, Life and Death will not function as North does to South or East to West. Rather, they fuse into a horizon that compels us onward.

Grief Assignment Prompt

I would very much like to know how you continue processing this line of thought. Below, I’ve modified the three lesson I enumerated above in order to make them more directly applicable to a discussion of grief. If you feel compelled, write up your response to one or more of the questions and put them in the comments below:

Lesson 1: Build on my claim that grief has no opposite. To put this another way, we do not need to have a static opposite to grief in order to process grief. What ideological or pragmatic concerns frequently trick us into constructing an opposite for grief? (For example, if we imagine that “health” is opposed to grief, then we begin to think of grief as an illness, as something from which to recover. What problems are bound up with that construction?)

Lesson 2: When is “close enough” good enough? You might agree with me that grief has no true opposite, and yet you may believe that it is helpful to assign a certain opposite to grief in order to continue caring for yourself. For example, you could assign “self-compassion” as grief’s opposite because, for you, grief is so closely entwined with self-scrutiny and impatience. Would your oppositional pairing then be “close enough” to prompt continued self-growth? Or does grief present a situation in which “close enough” and “good enough” don’t cut it?

Lesson 3: If you made your own children’s book about grief that utilized Coat’s pedagogical framework for Hippopposites, what oppositional pairings would you present? These pairings could all be true, or they could all be untrue. You might present them for consideration in order to help people question what grief ought to look like. Whatever your rationale, what pairings would you present? The only stipulation is that one of the pairings must always be “grief,” such that you will end up with your own version of the list I started above: Grief and Ease; Grief and Ignorance; Grief and Bliss; Grief and Lightness; Grief and Certainty.